25%

Many years ago, when I was a child, most treats were denominated in quarters, and a pack of gum cost only one. Then, a few years later, it cost 30 cents. This was when the world changed, when buying a treat became more expensive and more complicated. More fishing for loose change in the pockets, more adding and subtracting. It was the early 21st century and, despite avoiding Y2K, many things were going wrong, like Enron, 9/11, the dot-com bubble, Robert Hanson, Afghanistan, Iraq, and gum costing a nickel more.

The first quarter of this century is over, and the next five years are shaping up to be very eventful. This newsletter, to my chagrin, has not been very eventful, and I aim to change that. There is no deficit of material and drafts and ideas, but there is a surplus of caution and self-criticism.

On average, I write 10.23 paragraphs per day, and that average used to hover at 16. It is no surprise that all the pieces on this site range from 5 to 17 paragraphs — with the exception of the very first one, which weighs nearly 60. I could have published one piece every single day if I wanted to.

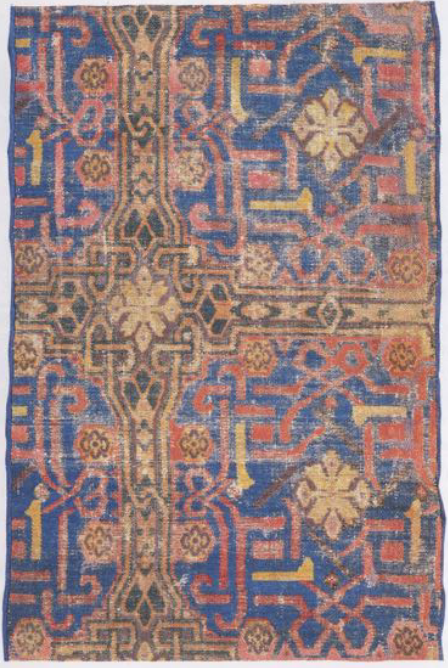

Know this, my hypothetical reader, I am silent because I care, and I care with the depth and conviction of a Japanese swordsmith or an Ottoman kilim weaver. You see, the Japanese warriors believed that their swords housed their souls. The Ottomans believed that their rugs were conduits between their souls and their god. I believe that my words — published and unpublished — contain fragments of my soul, but only the published ones can help our souls meet.

Time, it drips away, and with it so do we. As we drip away, so too do we drift apart. And the writing, it will not slow or reverse the drift — nothing can reverse the drip-drip of time. Each paragraph, each sentence, each word, it accelerates the drip, it accelerates the beating of the heart. The words do not bring us closer, they simply reveal how far apart we are, and, perhaps, the greater the distance the greater the beauty.

I look at some of my older writing, from years ago, and I feel like I am walking through a dusty attic or a rusty junkyard, stopping to look at abandoned once-loved toys and dead machines that once rumbled and breathed fire. Time does its part and the imperfection of my words spreads like vines — a different person wrote them and salvage seems futile. Potsherds and fossils are the unit of currency of the archeologist and paleontologist — detritus and residue are the most perfect things they will see in their practice. I wonder if we write now for the junkyard, for the archeologist, for the odd people who dive through dumpsters.

Even the moon has some of our long-discarded junk still on it, and it still fascinates and inspires people. The words we write will only become less perfect over time, and so, endlessly polishing a piece is a dishonesty against the past.

In fact, the most admired kilims are featured in a book by Christopher Alexander called Foreshadowing a 21st Century Art — they are hundreds of years old, torn, faded, ragged, frayed. Upon a glance, most of us would have mistaken them for junk. Maybe the true test of perfection, is when the inner harmony of something can be seen, in spite of the loose threads and tattered edges.

Plus 1%

This next year, we are going to go for a long meandering walk through the junkyard, because, I suspect, where I see failure or fault, others will see curiosity and inspiration. And even if the junk really is junk, the junkyard is the closest thing we have to a time-machine, and I have always wanted to write a time-travel story.